What emerging markets can learn from the West’s “unicorn factory”

TL;DR: There's a lot more running room left in EM, so founders and US VCs should take note and get beyond their provincial comfort zones.

This article was written for and exclusively published in the Realistic Optimist, a weekly publication making sense of the recently-globalized startup scene.

Get yourself a 1-month free trial here.

About this op-ed’s author:

Mark has led go to market in emerging markets for large and small companies, from Google’s initial push into maps in the mid 2000s to Facebook’s early mobile efforts and ultimately co-founding PayJoy, a Silicon Valley-based fintech, in 20 countries. He most recently served as VP of Partnerships at the Stellar Development Foundation, an organization focused on emerging market financial inclusion, where he currently advises.

He has also raised ~$100M in early stage VC, venture debt, and SPV debt financing across four companies he built, and advised companies on fundraising.

He now runs Next Billion Advisors, a global network of seasoned and rising digital entrepreneurs who collaborate regularly to help emerging market founders succeed. His views are his own.

Unicorn factory farming

Sam Lessin, an American VC, recently pontificated on the end of what he calls the “unicorn factory system”. He describes a configuration whereby each investor along the fictional assembly line packaged companies to raise their next round, omitting deep questioning of those same companies’ business fundamentals.

This system, he argues, has led to disappointing IPOs such as Bird, whose underlying unit economics did not stand the test of public scrutiny. Adding insult to injury, Lessin posits that the good companies to come out of that era, such as Stripe, were kept private while not-so-good companies were dumped on public markets via shady SPACs. In the US specifically, stringent antitrust regulation has also reduced big tech’s propensity to acquire startups.

The increasingly disenchanting exit path for startups on the factory line has created a nefarious snowball effect, where the entire sector’s attractiveness to LPs, employees, and would-be founders has decreased. The end of COVID-induced ZIRP (zero-interest-rate-policy) has also turned off the seemingly endless tap of funding the sector used to enjoy.

The result is American venture capital’s existential crisis, which Lessin predicts will usher in the return of more artisanal, less “predictable” VCs and companies.

Relevance to emerging markets

This still doesn’t seem to have afflicted emerging market (EM) startup ecosystems as severely, for various reasons.

First, local VC industries in many EM are still nascent. There is, in large part, a lack of local VCs capable of leading post-Series B fundraises. Despite American VCs’ 2021 foreign forays, most EM ecosystems still face a concrete undersupply of risk capital. This has coincidentally hindered the development of any such “factory” system, for the better.

Second, the exit path for startups in EM remains more attractive and profuse than in the West. This is illustrated in the chart below pulled from Pitchbook data.

Source: Pitchbook

Of course, a lot of this happened in China, so it is a good idea to zero in on a few regions that are not commonly discussed. According to a 2023 report by Magnitt, there were a record number of deals and exits in the “MEAPT” (Middle East, Africa, Pakistan, and Turkey) region last year . While more of a personal observation than a scientific demonstration, I suspect EMs’ comparatively lenient antitrust laws to be more conducive to a vibrant M&A market.

Third, most successful EM startups solve “real” problems. Capital constraints force local founders to find a real need, not invent one, and start thinking about profitability earlier than their Western counterparts. The convergence between increasing digitalization and a growing, more demanding middle class abounds EM founders with opportunities to explore.

This last point is strongly vindicated by none other than one of EM’s crown jewels, Nubank. The Brazilian fintech truly disrupted LATAM’s banking sector, beautifully riding the wave of the middle class’s desire for more advanced, digital financial products.

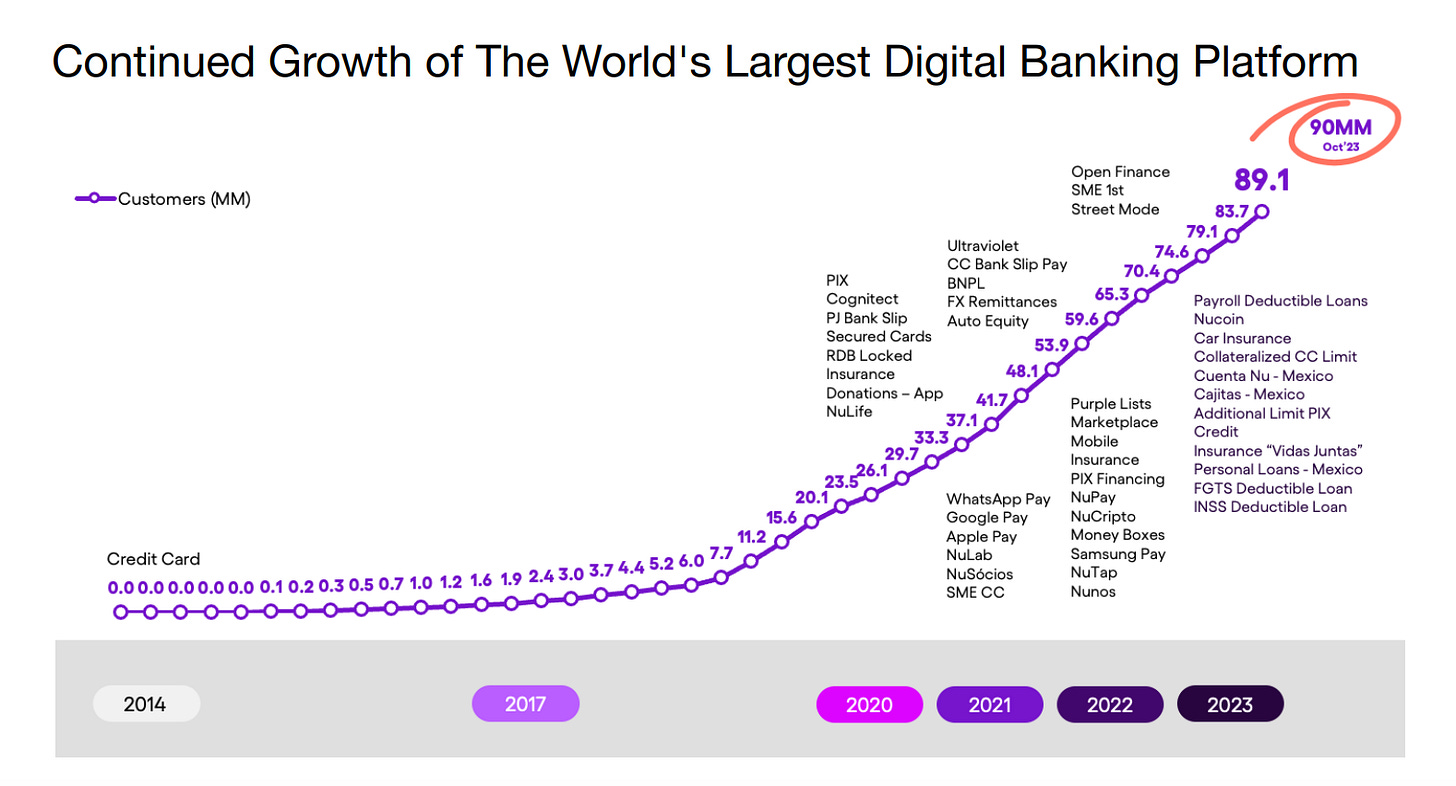

Since going public in 2021, “NU” has delivered solid growth, its future potential standing at the nexus of the region’s large potential user base and the plethora of new financial services (insurance, loans) it is rolling out. They have expanded regionally, but apparently did so with healthy unit economics.

Nubank sustained user and product growth

How EMs can avoid developing their own unicorn farms

As VC industries in EM mature, one could reasonably infer that they will become inclined to optimize themselves. After all, the Western venture capital scene developed the so-called unicorn factory system in part as an effort to standardize and professionalize a formerly niche industry.

Avoiding such a fate starts with maintained unit economics scrutiny. Standardizing the industry isn’t bad, as long as every investor in the “chain” isn’t practicing willful ignorance about companies’ business fundamentals. Increased investor standards ushered in by the end of the low-interest rate era should remain.

The potential for crypto

Shifting gears a little bit here. At both the Stellar Development Foundation and Next Billion Advisors, my work has reinforced my belief in crypto’s potentially game-changing impact, notably for EM startups.

With the majority of early EM startup successes being fintechs, and with embedded fintech gaining prominence amongst others, the way EM startups handle money is front and center. In many aspects, it is still a nightmare.

Cross-border payments are expensive, unpredictable inflation can put fragile startups under strain, and processing the continuous stream of new payment methods all represent challenges.

The infrastructure crypto is built on can assuage some of these pains. Simply put: cryptocurrencies enable a user to send traceable value over the internet, making the process of sending money to someone across the globe as fast and cheap as sending an email.

Crypto’s elementary, tangible potential for transforming the global financial scene has been overshadowed by scores of damaging speculative use cases and a polluted secondary market. As the sector’s bad actors recede, and in some cases go to jail, crypto’s less flashy but more useful use cases will retake center stage.

Developments in recent years are strengthening crypto’s real-world usability. Stablecoins, cryptocurrencies mirroring a fiat currency such as the $, are growing increasingly reliable. So-called “on and offramps”, processes used to convert fiat to crypto and vice versa, are augmenting in ubiquity and ease of use.

The progress is more than theoretical: Mexican fintech FelixPago has built its cross-border payment and remittance product using the Stellar network’s crypto rails in the background. The rapidity and cost reduction crypto enjoys over legacy financial infrastructure is unparalleled. Far from the cliché, crypto’s technological prowess undoubtedly represents one of the most significant financial innovations of this century.

What’s needed to usher in widespread adoption is refining usability. If a technology works but isn’t usable, it isn’t ready for widespread market adoption. What’s viewed as the “last frontier” here is people’s ability to actually spend the cryptocurrency they were sent. That remains a challenge in most places.

Particularly encouraging in that aspect is MoneyGram, a legacy remittance behemoth, onboarding to the Stellar network. MoneyGram has a truly global, physical presence through its network of agents charged with disbursing cash to the people money was sent to. By joining the Stellar network, MoneyGram “fills” that last frontier: people can send money via crypto rails and easily convert that crypto to cash through a MoneyGram agent.

Conclusion

Emerging markets are at an exciting juncture, where the growing middle class’s needs are being filled by innovative, home-grown startups. Startups optimizing the management of this newfound buying power, fintechs, are uniquely positioned. They represent both society-altering potential as well as strong investment cases.

Venture capital and crypto, two important actors in the advent of EM fintech, are facing a reckoning in the West. The venture capital sector has entered an existential crisis fueled by years of reckless and unimaginative investing, while crypto is coming to terms with its fraudulent first generation.

EM founders and investors have the benefit of watching this unfold from afar, and internalize the lessons needed to avoid such a fate. In short: keep venture capital imaginative but exigent, and focus on real-world crypto usability rather than niche, theoretical applications.

Financially tooling the “next billion” using lessons from my time in Silicon Valley has been my life’s work. The best advice I can give at this hour is “learn from our mistakes”.

Continue your reading with this relevant piece from the Realistic Optimist:

If you enjoyed this piece, consider a subscription to the Realistic Optimist here.

Over the past decade, the West has seen numerous unicorn companies emerge, but most of them haven't generated substantial profits. The US and EU markets can withstand significant setbacks, unlike emerging markets which tend to show signs of trouble much earlier, leading to a loss of investor confidence.

The upcoming five years will determine the success of the last generation of emerging market unicorns, and there's a strong possibility that they will have a detrimental impact on the ecosystem. I believe that emerging markets (any markets actually) should avoid chasing after inflated valuations and idiotic deals, as has been observed in the US and EU when interest rates were close to 0.